May Book Bracket

May was filled with a variety of books ranging from terrible to excellent to rather odd. Per usual, I ended up with a variety of both secular and religious books on my reading list.

Book Descriptions, Why I Picked Them, and My Impressions

The Blue Fairy Book, Edited by Andrew Lang

This is a collection of 37 classic fairy tales compiled at the end of the 19th century; part of a whole series of color-based fairy tale books, this one includes classics such as Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Hansel and Gretel, Aladdin and the Magic Lamp, Little Red Riding Hood, Beauty and the Beast, and Blue Beard. Other titles that might be recognized include Blue Beard, Rumpelstiltskin, "A Voyage to Lilliput" (based on "Gulliver's Travels") and Puss in Boots.Why I picked it up: This book came from a booth at the Midwest Catholic Family Conference. The reason I acquired it was because multiple books I'd read about C. S. Lewis and Tolkien referenced the fairy tales collected by Andrew Lang as something of precursors to the works of those authors. In my readings, it seemed like the blue book in that collection was the most frequently mentioned of any of the colors (perhaps followed by the green book?).

My impressions: These are about as classic as fairy tales can get. I think the editor altered the stories so that there weren't any fatally shocking elements, but I still found some to be uncomfortable reading. There is a certain quality to fairy tales in which some things are just weird, but some things end up being disturbing. Specifically, there are instances of violence which feel as shocking as they are bizarre. I'm not saying that they don't belong in the story; I just want to caution those who would pick up this book for a family read. I would recommend that, if read, these tales would be best enjoyed as a family read-aloud so that adults could discuss some of the trickier moral points or skip over some of the gorier sections. It was an interesting dive into classic fairy tales, but I did not enjoy most of them nearly as much as my beloved MacDonald tales, "The Princess and the Goblin" and "The Light Princess." There were some pleasant surprises that weren't too unnerving, including The White Cat, Snow-white and Rose-red, and Felicia and the Pot of Pinks. I did skip over Hansel and Gretel (never liked much) and "A Voyage to Lilliput" (disliked Swift's original satire rather strongly).

The One Thing is Three: How the Most Holy Trinity Explains Everything, but Michael E. Gaitley, MIC

This book was written as a sort of "retreat" for lay persons who don't have time to dive deeply into theology. It tackles the "big questions" of life, as well as the "hows" and "whys" of living the Catholic faith, but not in a way that's meant as apologetics.

Why I picked it up: I received this book for free from a day-retreat at my local retreat center. It looked like it was something I "should" read. I also wanted to clear yet another title from my pile of "to-read" books sitting on my shelf.

My impressions: This book was a mixed bag. It has solid theology and I gained some excellent insights from it - one of the main takeaways being that I need to go out and share my faith. However, I can't say this book rocked my world. The author used a more "conversational" tone and lots of summary phrases to help the reader keep the information organized and prevent it from getting to cerebral, I'm guessing. Unfortunately, I found this style a little off-putting and a slight distraction at times as I wondered how many words shorter this book would have been if its content had not been presented in this manner. I skimmed just a few parts here and there and sometimes zoned out, missing the meaning of the words I was reading. I liked the post-conclusion section that included recommended resources to explore, ranging from the Mass and Ignatian spirituality to works of "sacramental imagination" such as the "Chronicles of Narnia" and "The Lord of the Rings" series. I don't know if I'd necessarily recommend this book, but I certainly would not discourage others from reading it. This book took some perseverance to get through, so I wouldn't recommend it for anyone under college-age.

The Giant's Heart, The Golden Key, by George MacDonald

Fairy tales by the same author; one about children caught by a giant and their adventure in escaping him, the other about two children on a quest to find a special land which can only be reached by using the boy's golden key that he had found at the end of a rainbow.

Why I picked them up: A friend, knowing my affinity for other of MacDonald's fairy tales, recommended that I read some more of them.

My impressions: The main thought that came to me is that MacDonald has a weird fixation on grandmotherly figures giving children baths; it happens in most of his fairy tales that I have read, with I think "The Giant's Heart" and "The Princess and Curdie" being the only exceptions (the princess of "The Light Princess" doesn't receive a bath per se, but she spends every second she can in the lake, so I'm counting it). These fairy tales were alright, but they weren't "rave-worthy". "The Giant's Heart" has a moment where the narrator talks about the giant crunching on children like raw turnips that I found a little upsetting, but otherwise was a decent read. "The Golden Key" definitely felt like an allegory and shortchanged the plot in favor of what I guess was symbolism. These stories might be nice for older children to read or to read as a family, but they're not stories that I feel are "must-reads".

The Napoleon of Notting Hill, by G. K. Chesterton

This first novel by prolific writer G. K. Chesterton tells of the literal battles fought for independence by the neighborhoods of London; set in a futuristic London that is actually contemporary London.

Why I picked it up: An author I enjoy reading, Joseph Pearce, gave a talk about distributism that I found interesting and I knew that this book is touted as a defense of that economic system. I also was not quite ready to dive back into easier fiction after pushing through "The One Thing is Three", and this book fit the bill.

My impressions: This is certainly not Chesterton's best novel, but his had the hallmark sense of wonder and the ridiculous that is found in his fiction. I appreciated these childlike elements, but I found this book lacking in terms of being a good story. I also felt like the sense of the ridiculous was not incorporated well into the story as it seems to be in his other novels; rather, the bizarreness of it seemed ludicrously bizarre at times to me and I found myself siding with the antagonists a good part of the time - the main characters certainly seemed like crazy men to me. The book also failed to strike the right notes with me by making little of the blood spilled on account of a neighborhood's identity - there's certainly no just war theory at work here. I can appreciate the wild creativity of wondering, "what would it be like if my suburb wanted to secede and make itself a sovereign state by the use of only antiquated weapons?", but the execution of the scenario did not work for me. The final chapter especially showcased some weakness in storytelling and descended into preaching between two voices that argued different perspectives on the meaning of Notting Hill's endeavors. I could detect the sections that distributists might appeal to, but I felt that message was swallowed up by the philosophical last chapter. I don't think I would really recommend this book unless it were to someone who was very into Chesterton and felt the need to explore one of his earlier works.

Seven Lies About Catholic History: Infamous Myths About the Church's Past and How to Answer Them, by Diane Moczar

Seven sticky subjects that are often brought up by non-Catholics are explained and debunked by a history professor.

Why I picked it up: This was one of the books I acquired from an irresistible $5 TAN book sale. I wanted to know more about these difficult arguments that I encounter now and again.

My impressions: This book helpfully explained both the accusation and the response - it presented the verbage Catholics might hear from non-Catholics and then discusses why these accusations are not really problematic. The author did well to note that, yes, in many of these situations, there were egregious and sometimes immoral errors, but perhaps not to the degree the secular world thinks. However, is it possible that the author's conclusions are influenced by her desire to defend her faith? I think it is possible, but unless I were to take the time and do the work myself of diving into historical texts, I couldn't verify that. I would like someday to have an unbiased look at these topics from a non-Catholic scholar, but until then, I think this is a fine book that does much to inform Catholics and give them talking points when these subjects come up. I recommend this book for high school readers and up, especially for Catholics, but I think this book could be of interest to non-Catholics as well.

Mr. Popper's Penguins, by Richard and Florence Atwater

Mr. Popper is obsessed with all things polar and receives a penguin as a gift from an Antarctic explorer. He and his family (and the growing brood of penguins) achieve fame after training the penguins to perform an act.

Why I picked it up: I obtained about 20 children's chapter books from a retired teacher and I keep them in my speech room. I figured it would be good to know what exactly I have on my shelves, so I periodically pick one up to read.

My impressions: This was not a great read. It was thankfully quick (I read it in the space of an hour or two), but it was very dull. It seemed less like an engaging story and more like a thought experiment on the question of, "What would [x] family do if penguins entered their lives?" It received a Newberry Honor recognition and has been turned into a movie (which I have not seen), which made me even more surprised that it was so dull. There is nothing morally problematic with the book, although Mr. Popper shapes up to be a less-than-admirable father figure, a man who works only half the year and is content to let his family subsist on beans for the other half (at least until the penguins come along). I wouldn't recommend this book, but maybe someone who can't get enough of penguins in their life might appreciate it.

Fever 1793, by Laurie Halse Anderson

Mattie Cook experiences the yellow fever pandemic that overtook Philadelphia in the titular year.

Why I picked it up: This book caught my eye at a bookstore in the last year and I remember having seen it around at school as a tween/young teen without ever having read it. I did not purchase it because I wasn't sure if it was a keeper, but I added it to my "to-read" list.

My impressions: Well, this was an apt book to read during COVID-19 quasi-lockdown, and some of the similarities between this book and reality are striking. COVID's primary symptoms of respiratory issues don't seem quite as disgusting as the vomiting, jaundice, and yellow eyes of yellow fever, but both are/were life-threatening illnesses that involved fevers. The story, which followed the small group of Mattie's family and friends, kept my interest, although I wouldn't say it was a suspenseful page-turner. I enjoyed the coming-of-age element because it depicted Mattie's maturation without feeling like it the author was screaming at me to notice the changes. Mattie's character development is clear, but I did not find it overt - I don't know how it would appear to others. I found that almost the entire book felt real and believable until the end, where an arrangement is reached by certain people who I'm not sure would actually have been able to go into business together in that period. I felt like the author did her research, including quotes from literature produced at that time, particularly letters by Philadelphians. Lots of people die due to the epidemic, including one beloved character, so more sensitive readers might not be ready for this book or the descriptions of the illness it contains. The main character has something of a mini-crush (as one friend would say, a "crinkle") on a young man and I noticed just a part or two where she mentions something like she "shouldn't look at him as if he were a racehorse for sale," although there's nothing racy in the book. I think this book would be appropriate for readers at this reading level and older, unless they are sensitive (or highly concerned about the COVID-19 epidemic).

St. Francis, by G. K. Chesterton

This small book considers St. Francis' life, not in its fact and straight history, but rather in the typical G. K. Chesterton way of considering the bigger ideas and meanings.

Why I picked it up: I purchased this book at some point on Amazon.com. I need to be more careful in future about cheap Amazon books because this was one of the weirdly-reprinted works that was rife with distracting typos. Even the classical painting of St. Francis on the front...depicts the wrong Saint Francis (St. Francis Xavier), not Saint Francis of Assisi.

My impressions: This book was not what I expected. I would definitely say this should be a companion to a biography of St. Francis, not an actual biography. As a standalone work, I found it hard to get into, even though I generally enjoy GKC's writing. My favorite part was a quote: "It is as rational for a theist to believe in miracles as for an atheist to disbelieve in them." These one-liners were one of the first things I loved about Chesterton. I'd recommend this book really only as a supplement to a biography of Saint Francis.

Emily Climbs, by L. M. Montgomery

The second book in the "Emily of New Moon" series follows Emily, a little older, as she boards with a different aunt for high school and continues writing, writing, writing and submitting her works in hopes of seeing them published in magazines. After many everyday occurrences are lived through (and another "second sight" incident), Emily is offered a chance to work with a New York publisher. She turns down the opportunity because she is so rooted in New Moon and wants to be a truly Canadian writer.

Why I picked it up: I remembered that I read the first book in the series last summer and figured it was time to read the second one.

My impressions: I find this series sooo much better than "Anne of Green Gables". I haven't figured out why, but I ate up this book. I think maybe I connect with Emily's experience "clan" of Murray relatives. I know my relatives are far more pleasant than hers, but I hope my family pride and loyalty doesn't blind me to anything. I liked watching Emily mature and found her creative drive fascinating. I wonder if most successful authors share her experience of desperately needing to write, or if there is perhaps some variety (which I hope for, for the sake of my own creative dreams). I'd recommend this book for those who enjoy the "Anne" series, but with a few caveats: I didn't quite like some of the ideas of religion expressed in the book and thought the main "second sight" incident might need some parent explanation - or at least parental awareness - particularly for younger readers. I just don't know what to think of such situations when they come up. Otherwise, I found the book very enjoyable.

Carry On, Mr. Bowditch, by Jean Lee Latham

This Newberry Medal-winning book chronicles the life of American navigator Nathaniel Bowditch. Though he showed great aptitude in mathematics, he had to leave school at an early age and take on an indentured position, during which nine years he educated himself in a variety of subjects, including languages, mathematics, science, and astronomy. He spent some time on ships, developed a better way of calculating longitude, and taught the crew about navigation, eventually writing a more accurate navigation book than anything available at the time.

Why I picked it up: This title was mentioned in "The Enchanted Hour" as a worthy book; the Newberry Medal was encouraging as well.

My impressions: I don't usually like books that lack plot, but I found "Carry On, Mr. Bowditch" interesting and even compelling at parts. Books about sailing have their own special flavor and I enjoyed it very much. I don't know how much of the book is factual and how much "poetic license", but the main points seemed to match up pretty well with the Wikipedia entry for the main character. I'd recommend this book to any reader who can read at this level, but keep a dictionary handy for unfamiliar sailing terms. A good luck charm is discussed once or twice, but comes into the story very minimally. I can see myself reading this again someday.

Bracket Play

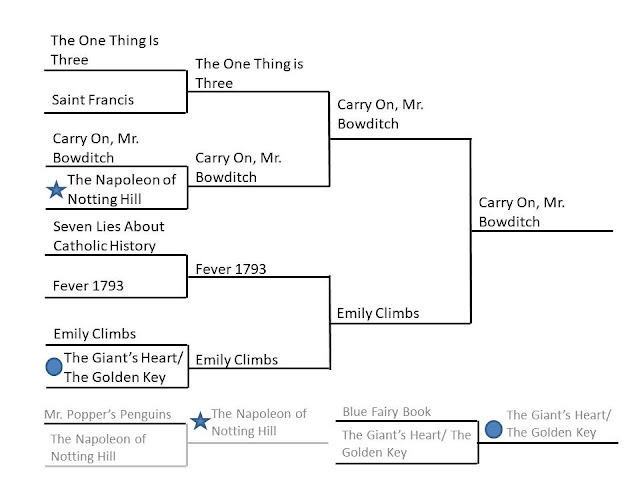

Again, here is May's bracket:

This bracket looks a little different than usual because I had a weird number of books - 10 - that did not fit easily into a bracket. I had two play-in "games" between the four weakest competitors. GKC's "The Napoleon of Notting Hill" breezed past the very dull and lacking "Mr. Popper's Penguins" to make it to the first round, and after a little consideration, the "Blue Fairy Book" fell to MacDonald's fairy tales. The "Blue Fairy Book" failed largely due to the inconsistent qualities of the many tales included - some were weird, some concerning, some classic and familiar, and a few surprising and new. It was too much of a mixed bag when compared with just two of MacDonald's longer fairy tales. Perhaps it wasn't a fair match-up, but bracket can never create a completely even field.

Both play-ins, not surprisingly, failed to make it past the first round, where they were matched with the two books that would eventually become #1 and #2 for this month's book bracket. GKC's "Napoleon" was a bit of a drag and had some weak storytelling, whereas "Mr. Bowditch" managed to work in unfamiliar terminology and bring a bygone age to life without sacrificing pacing or reader interest. "Emily Climbs" possessed a comforting atmosphere that hit in a homey way, whereas "The Golden Key" turned into something of a less-accessible allegory. Two religious books, "The One Thing is Three" and GKC's "St. Francis" went head-to-head and GKC's work again lost out. Both books were somewhat dry and took a bit of perseverance to get through, but I found Father Gaitley's book better organized and focused than "St. Francis," which did failed to explain major points of St. Francis' life or, if it did address some, did so in a nonchronological way that ended being somewhat confusing to this reader, who has not brushed up on her St. Francis knowledge for a while. Finally, it was a toss-up between "Seven Lies About Catholic History" and "Fever 1793". As noted above, both books had flaws, and it was very much a case of comparing apples to oranges. I eventually decided on "Fever 1793" because I enjoyed it more (I lean towards fiction anyways in my personal preferences) and figured it would be palatable to a greater number of readers.

In any case, it did not matter; either book would have lost to "Emily Climbs" in round two. There were no concerns on my part about the historical accuracy of Emily's tales and it was again the charm of the narrative that captured my heart. "Fever 1793" held my interest, but I cannot say that it found a deep appreciation from me like "Emily Climbs" did. Again, a spiritual book did not beat out a work of fiction that I found much easier to get through. I was eager to keep reading "Carry On, Mr. Bowditch" but did not share the same feelings for "The One Thing is Three".

"Carry On, Mr. Bowditch" ultimately won because of its lack of questionable content and its walking pretty well the line between telling an interesting story and showing the characters develop. "Emily Climbs" certainly got down to Emily's thoughts more than "Mr. Bowditch", so she had the benefit of presenting a more nuanced and full character study. However, the fact that I could detect changes in Nathaniel Bowditch without reading excerpts from his written journal every so many chapters shows a different kind of storytelling strength. I can see myself returning to "Carry On, Mr. Bowditch" in future, especially if I had the chance to read it aloud with children. It's a story that both boys and girls can enjoy, which is not something I would think likely of "Emily Climbs".

Books Attempted and Put Down

Catholic Viewpoint on Censorship, by Harold C. Gardiner, S.J.

This book considers the philosophical reasons and theology behind the Catholic position regarding censorship, as well as what the several attitudes towards censorship in the United States were at the time of publication.

Why I picked it up: Believe it or not, I was actually interested in this book when I picked it up on sale at a local Catholic bookstore. Censorship has ties to my perennial questions regarding the role of entertainment in the Christian life - are there books that are inherently bad for all persons? If so, how is that determined? And by whom? - so I wondered what would be revealed in this book.

Why I put it down: This book is "vintage," insofar as censorship looks very different now than it did when this book was published in 1961. At that time, there was an "Index of Forbidden Books." With some Google searching, I found out this was abolished in 1966, although what that means for censorship I don't really know. I experienced a few moments of minor shock as my modern sensitivities recoiled from any prohibition on what persons choose to read or not read - isn't that a violation of free will? I asked. The book answered that question, but I'm not going to work that hard to delineate it here. Even though I didn't make it through the book, I read enough of it to think that I should eventually research more on the ideas I encountered...including such questions relevant to our time regarding license (the freedom to do what is right) and the rights and duties of legitimate authority. Consider, if you will, this timely quote: "Freedom of the press and of expression can, in circumstances, be as legitimately subject to restriction as any other freedom - that of assembly, for instance, in times of catastrophe or plague." If that's not a statement to get all political parties worked up, I don't know what is. Someday I would like to know more on these subjects, but not today...although I anticipate it will be a handy source in the future.

Wildwood, by Colin Meloy, and illustrated by Carson Ellis

This book, created by a husband-and-wife team, follows Prue and Curtis as they explores the forbidden "Impassable Wilderness" of Portland, Oregon in the attempt to retrieve Prue's kidnapped one-year-old brother. Animals talk and have built a society along with humans in the heart of this area, which they refer to as "Wildwood".

Why I picked it up: I saw this book in several places and found it intriguing. The book came up at some point as one that people who liked "The Chronicles of Narnia" might appreciate, so I decided to give it a try.

Why I put it down: After 70 pages, I still wasn't really "into" the book. I decided to look up the plot on Wikipedia and realized that I probably wasn't going to find the next 430 pages much better (yes, it's an unwieldy monster of a book). The writing wasn't bad, but it was what I might call "blah", and the culture of the Wildwood beasts - at least, what I had encountered up to that point - was not well developed. I lacked the sense of wonder and adventure that permeates books like "The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe" and was further disenchanted with the prospect of continuing my read by learning that Black Magic was used to bring someone back to life. Granted, I think that part is recounted as history rather than being described in the book, and the villainess is the one who used it, but any mention of magic raises a red flag for me (even though it's not a death knell). I was disappointed that the book wasn't as good as I had hoped, because the illustrations are amazing and several full-color plates are aesthetically gorgeous. I wouldn't recommend this book both for the content concerns as well as the lack of engagement I experienced while reading it.