November Book Bracket

November was another five-book month, but some of the books were pretty intense in length as well as in the mental engagement required to read them.

My Reviews

Edith Stein: A Philosophical Prologue 1913-1922, by Alasdair MacIntyre

A philosopher writes about the philosophy of the Catholic Saint, Edith Stein, primarily from the perspective of history and her lived experiences prior to her life as a Catholic.

Why I picked it up: This book was required reading for a philosophical class I'm auditing.

My impressions: This is definitely a book about philosophy, but not from the perspective of trying to give a general account of philosophy or even an account of an entire movement. The author, MacIntyre, a philosopher and convert to Catholic, explains only the philosophical foundations relevant and necessary to understanding Stein's own philosophical thought. That doesn't mean I actually understood everything, but I appreciated that he limited himself in this scope. It was interesting to read about various factors that probably influenced her own thought and her eventual conversion to Catholicism. I thought the author was fair in his analysis of Stein's philosophy, giving her credit where it was due, but also pointing out the shortcomings of her philosophical compositions. I don't think I'd necessarily recommend this book to people to read - certainly not just for fun - but I can think of at least one person who might like to give it a try because it has to do with a beloved saint. In spite of the difficulty of wading through philosophical terms, I did feel the book made accessible Stein's work, which would otherwise have proven far too daunting for me to ever consider really diving into.

My Bondage and My Freedom, by Frederick Douglass

A well-known abolitionist grew up as a slave in Maryland, sought to educate himself as much as possible while enslaved, escaped to the free states as a young man, and began a career dedicated to ending slavery.

Why I picked it up: This book was required reading for a philosophical class I'm auditing.

My impressions: Douglass was an extremely astute man, and his excellent prose testifies to his intelligence. His observations about his own development and his description of the entire slavery system provided me with lots of food for thought. One could say that his reflections made me reflect. I had known, in a sort of abstract way, that slavery was wrong, but reading the personal account of someone who experienced it brought home to me the incredible EVIL of the institution of slavery. I am so grateful that we live in a nation where it is outlawed, but it also makes me more sensitive to the injustices still perpetrated in our society. Some of the best (and worst, excluding descriptions of horrible things done to people of color) parts of the book were Douglass' character sketches. He observed how circumstances, influence, and even the practice of "owning" another person changed the people he encountered. I would highly recommend this book to anyone of upper high school age or older, so long as they were aware there are some very troubling descriptions of the horrors of slavery included.

First Draft, by An Aspiring Author

A Robin Hood fan-fiction considers the legendary tales from the perspective of a stuttering Maid Marian, a timid woman who finds herself waylaid in Nottingham when all she wants is to reach a convent to live her life out in silence.

Why I picked it up: It was written, but had not been read by the author as a single work.

My impressions: I am shocked that the author asked her friends to read this first draft. The fact that three people read this work and still wanted to be her friends is a testament to the strength of their character. This work was awful. I would definitely not recommend reading it at this time. The author's attempts to make the language sound archaic made for some stiff and awkward reading. There were some pretty egregious historical inaccuracies and plot holes, manifesting specifically in a tendency to develop characters halfway before dropping them completely from the narrative, only to have their names dropped again in the last chapter. There were some definite slow parts, but a few sections showed real promise. The archery tournament had some decent build-up of suspension and pacing, and the tension between Marian and Robin Hood was not without a little merit. This work is a first-class example of why first drafts should not be widely read. I anticipate something like an eighth or tenth draft, with some major reworking of different sections, might go a little better. The story has some potential. It would take something of a miracle to make it a real blockbuster of a tale, but with a lot of work and over time, it could end up being a work with which its author is satisfied.

Wild Animals I Have Known, by Ernest Thompson Seton

A naturalist shares a collection of quasi-fictional short stories about wild animals (and domesticated creatures with a wild side) that he developed from his encounters with them.

Why I picked it up: I saw a FB post once that compared required reading for eighth graders a century ago with required reading for modern day eighth graders (or something along those lines). This book was on the list of the bygone century and it piqued my interest. I saw it on our bookshelf at home and picked it up as a sort of fluff-read to accompany the heavier academic works that have been my focus lately.

My impressions: This was a easy read, but it also made me think about the nature of man's relation to wild creatures. In short, it was pretty perfect - thought-inducing, but endearing and not difficult to work through. By showing the personalities of creatures ranging from crafty wolves and foxes to courageous bunnies and partridges, the author makes a good implicit case for preserving wildlife instead of hunting it down thoughtlessly or ending animal lives cruelly. I rejoiced in the author's turn of phrase several times, including when I read a passage about a raccoon that, like old-time monks, was rumored to consume a meatless diet, but needed only an opportune chance to end his abstinence. The stories almost always ended with the death of the storied creature - in the introduction, Seton notes that the story of every wild creature is a tragic one - which made for some sad moments, but it was fascinating to consider the incredible intelligence of the animals. This book rekindled a sense of wonder towards animals that I have not felt for a while. In short, this is a fantastic little book and, while it's at a reading level that middle schoolers could navigate, I would warn some parts might be hard on the emotions for youngsters - especially for animal-lovers. Those sad parts make me think that this would maybe not be the ideal read-aloud. I would recommend this book to my friends as something to reconnect them with a love for nature or even just as an easy getaway in the midst of the heaviness of adult life.

Stages on the Road, by Sigrid Undset

Nobel-prize-winning author Sigrid Undset wrote this collection of biographies and theological considerations as separate pieces for different publications. She writes about Ramon Lull, Saint Angela Merici, St. Robert Southwell, St. Margaret Clitherow, and about gossiping and marriage.

Why I picked it up: This book was required reading for a philosophy class I'm auditing.

My impressions: To be honest, I'm not quite sure what to make of this work. As an introduction to some Medieval and Renaissance figures of the Catholic faith, it was interesting. The essays on gossip and marriage were good as well. However, I don't know exactly how to consider it as a whole work. Should I just take it as a collection of some of Undset's shorter, nonfictional works, and nothing more? Or is there more to this grouping of biographies and topics than I appreciate right now? I'm looking forward to hearing what comes up in the class discussion about this book. I did not like the two biographies about the Catholic English martyrs as much as the rest of the book because I find that period of Church history to be a downer. I know that there are beautiful witnesses to the faith from this time period, but the persecution of the Catholic faithful hurts me. Also, I feel a little weird that this is my first reading of anything by Undset, and not her ultra-famous "Kristin Lavransdatter." This book would be good for high schoolers and older, although I would put a cautionary label on final essay about marriage if the reader is sensitive to the topic of suicide, which is brought up as an example in that part.

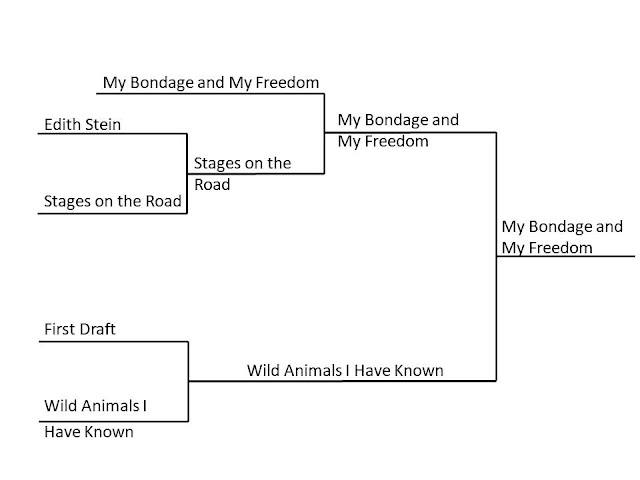

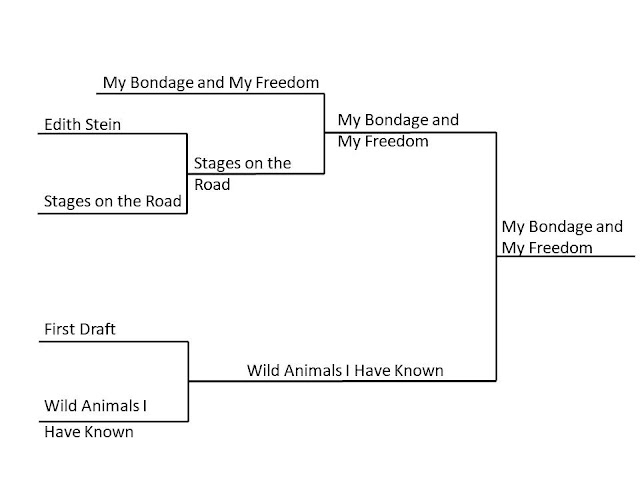

Bracket Play

Frederick Douglass's "My Bondage and My Freedom" received a pass on the first round because of its excellence of prose and ideas communicated. MacIntyre's "Edith Stein" fell to Undset's "Stages on the Road" because of the difficulty of the former's prose and the reader engagement developed in the latter. The "First Draft" fell without a fight to Seton's book on wild animals biographies for every reason.

Douglass' work went on to dominate the next two showdowns for the reasons listed above: the writing is superb, the work made me think, and it's one that I would recommend to other people to read.

Books Attempted and Put Down

The Walking Drum, by Louis L'Amour

This work of historical fiction centers on the adventures of the British/Celtic Kerbouchard in the world of Medieval Europe and beyond.

Why I picked it up: I found this book at a garage sale and wanted a break from the heavier reading I was doing for my classes.

Why I put it down: This book did not really work for me. It had adventure elements, but I couldn't say that I really liked the main character. I wasn't invested in the book after 60-some pages and decided to move on to another book. I may come back to it in time, but probably not for a while - at least, not until I knock out some newly-acquired books on my shelf.