June Book Bracket

I did a lot of reading this month: 14 books. I love summertime.

Book Descriptions, Why I Picked Them, and My Impressions

Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, by Maryanne Wolf

A neuroscientist and expert on child development explains the historical development of reading, what happens in the brain when a neurotypical person reads, and the facts and mysteries of dyslexia, when people have difficulty learning to read.

Why I picked it up: Because of my job, I have learned some about reading development and reading disabilities and this book was mentioned in several different experiences as good "further reading."

My impressions: I would say that this was a good read. The book is well-organized and well-researched, although some parts were a little technical and slow. I found the historical development of reading particularly interesting - for example, I did not realize that we still haven't translated some ancient writing systems. I had supposed that there weren't too many linguistic mysteries left out there, but I was wrong. The middle section, which considered the reading brain, was neither terribly painful nor terribly interesting to me - I have to note that I've had more experience with medical terminology for different areas of the brain, etc., than others may have had. It probably isn't everyone's cup of tea. The book was published in 2007, so some of the data might be dated already - I'm not sure what the latest studies on reading or dyslexia say. I found the title irritating - the author explains why she chose it, but I don't like that it still felt only vaguely connected to what she was discussing. Proust was a French author, and I can't recall why exactly she referenced him, but it had something to do with him writing about the power of reading, it's ability to change your thinking, etc. She refers to squids because apparently scientists studied giant squids in the 50's and 60's and learned things even from squids who couldn't swim very fast - I guess Wolf was trying to connect squids to dyslexic readers and how we're learning about reading from the brains of people who can't read quickly or well. All that aside, this book might be of interest to those who want to learn more about reading from a scientific and historical perspective. The information might be familiar to those already steeped in reading acquisition and reading disabilities, and it might be a little slow at least in some parts for readers.

St. Peter's Bones, by Thomas J. Craughwell

Craughwell tells the story of the bones of Saint Peter, first pope of the Catholic Church, from his death until their rediscovery underneath St. Peter's Basilica during excavations conducted during the 1940's-60's.

Why I picked it up: I had intended to read a different book about the same topic ("The Bones of Saint Peter) because I think it was recommended in George Weigel's "Letters to a Young Catholic", but I can't remember for sure. When I went to the library to pick it up, the book I'd originally settled on looked like it had a publication date of 1920-something and therefore wouldn't have had any information about the major excavations that happened after its publication. I went with a more modern-looking (and more condensed) book on the shelf a few inches away.

My impressions: I think this is a great introductory book to the kind of crazy story about what happened to St. Peter's bones. It covers the essentials and doesn't waste time, packing the tale and two small appendices into a whopping 120-some pages. I like how the author interspersed the 1940's-60's excavation narrative with necessary background information about who St. Peter was, the veneration of relics, and catacomb history. The 20th century portion made me begin to wish that this was made into a movie. Granted, by the end of the book, I thought maybe it wouldn't be quite fascinating enough for a movie, but there were definitely some exciting moments and even archeological drama. I did not realize that the bones they've settled on are not definitively "proven" to be those of St. Peter beyond all doubt, but the case is decently solid. This is a quick read and I'd recommend it to high school students and older, and if it is intriguing enough, the author drops enough names and scholarly works on this specific topic that the curious reader could continue to explore.

Why I am Catholic (And You Should be Too) by Brandon Vogt

A convert explains the reasons he joined the Catholic Church at the end of college: it is the true Church, it is good, and it is beautiful.

Why I picked it up: I think it's a good practice for me (and other Catholics) to review the reasons why a person would believe Catholicism is the true faith.

My impressions: This is one of the best apologetics books I've come across in a while, and I say that because it is a convert speaking to those who might be outside the Church. In some apologetics books, I get the sense that they're written for people who are already baptized believers and give arguments and talking points so that the reader can evangelize. In such books, I find some beliefs are taken as "givens" on the part of the reader and not really explored. Vogt's book doesn't assume the reader has accepted any of the Church's teachings, and therefore he voices his reasons differently than the other writers I've come across on this topic. I'd recommend this book to just about anyone, both Catholics and non-Catholics alike.

The Sign of the Beaver, by Elizabeth George Speare

In the wilderness of colonial Maine, young teenager Matt must guard the family homestead as he waits for his father to return with the rest of the family. Native Americans help him survive while he is alone, and he learns much from his peer, Attean, and Attean's way of life.

Why I picked it up: This author was recommended in some recent reading lists and I liked the sound of a "surviving in the wilderness" story.

My impressions: I liked this book; it has the "survival" element I was looking for, but it also did not shy away from hard questions regarding racism and race relations in colonial America. I have to admit some of the questions and conversations were a little uncomfortable for me, but I liked that it challenged me, too. One of the main ways in which racial issues come up are through the reading of different passages of "Robinson Crusoe", an activity that plays a not insignificant role in the book. I have never read that book myself, but I think I would be more aware of racial stereotypes if I were to read it because of Speare's book. I imagine something similar might happen for a young reader who is not familiar with "Robinson Crusoe" at all. I did notice that the author raises questions on this topic, but is not necessarily forced to answer them; in a way, history shows how real people answered those questions, and things went terribly for Native Americans throughout westward expansion. In any case, even if the character Matt still wrestled with those questions, the end of the narrative shows that he is more embracing of indigenous peoples and culture than is his family. The term "Indian" is used in this book instead of "Native American", but I can't tell if it is because it was written before political correctness became big or because that is the term the characters of the time would have used. I think this book is fairly safe to read, although parents might just want to be aware that Attean shares a creation story similar to that of the Biblical story of Noah, in case they want to discuss or be ready to field questions. I think this would be a fun book to read aloud.

One Word That Will Change Your Life, by D. Britton, J. Page, and J. Gordon

This book outlines the process of choosing and implementing the "One Word" program in one's life.

Why I picked it up: I am working on moving up the payscale and completing an online study of this book helps me towards that goal.

My impressions: I got very strong self-help themes from this book, which I found rather a turn-off, but I can see how this could be a very powerful tool for those who give the process a try. While reading, I realized that I first heard of this concept of choosing "one word" to shape the coming year about six months ago at a Theology on Tap talk. I did not try it out then. The process is simple, which would help people actually try it and keep working at it, but even after reading it I did not feel invested in it myself. Even so, I think this would be a great book for people who need some sort of change in their life or want to approach New Year's resolutions in a new way. There's no guarantee it will work, but if reading a super short 100-page book with lots of pictures and large text gives someone a chance to really improve their life, why not?

Purposeful Play: A Teacher's Guide to Igniting Deep & Joyful Learning Across the Day, by K. Mraz, A. Porcelli, and C. Tyler

This text explores the importance of play to learning in a school setting.

Why I picked it up: I am working on moving up the payscale and completing an online study of this book helps me towards that goal.

My impressions: I can't say I loved the book, but it was very informative and provided lots of examples and practical applications. It was drier than what I like for my summer reading, but a lot better than many textbooks I've worked my way through. I found some values espoused in some of the example situations (what makes a family?) conflicted with my own beliefs and concerned me about what students might be learning in a public education classroom as far as morals go, but for the most part, it had unobjectionable content. I caught some references (e.g., Ninjago, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Star Wars), but missed others, such as characters in unfamiliar show or movies (Wolf of Wall Street? Ferris Beuhler's Day Off?). I appreciated some of the points made, but nothing that made me think, "Wow, I need to change how I'm doing things at work!" It was not particularly memorable, but it could be a helpful resource for those who work in a school setting.

The Shining Company, by Rosemary Sutcliff

Sutcliff created a story out of a seventh-century British poem, "The Gododdin", that tells of a company of 300 warriors and their servants (shieldbearers) taking on an invading Saxon force many times their strength.

Why I picked it up: I've had this author recommended to me, she being a writer of children's historical fiction, for which she has gained great recognition in that genre. This book was available at my alma mater's library and sounded interesting.

My impressions: This book deals with lots of violence and death - as these adventure stories often do - but it lacked the lighthearted atmosphere I am used to encountering. This book definitely had a serious, and even grim or gritty feel throughout it. If you are familiar with Tolkien's "The Lord of the Rings", think of the feel of the land and people of Rohan, and the heaviness of going into battle without real hope of success. I liked that the author definitely researched the time period well and had the characters speak in a style that felt antiquated, even if it made their conversation choppier to my modern ear. I like that Sutcliff balanced the main character's thoughts with lots of action - some books fall into a trap of being all in a character's head, or not in there much at all, and "The Shining Company" did not fail in those areas. However, I cannot say that I found the plot compelling. Some sections were episodic, and while they had their purpose (Sutcliff connects ideas to events to characters throughout the length of the tale), they drew away from the main action which, being training for battle, going to battle, battling, and the denouement action, was pretty plain. The names are drawn from the original poem, but there were so many and the spellings did not match up with the pronunciations (according to the pronunciation guide at the beginning of the book) that it was burdensome to remember how to say them. Some elements might be problematic for young Catholic readers, as the characters lived in a time where people were often Christian, but still held on to some pagan beliefs and ideas of the past. I found the "mercy killings" of dying warriors concerning as well. This book felt like a story made out of an epic, rather than a story that was meant to achieve the heights of the epic genre. I think mature middle school children who understand or are not troubled by the uncomfortable circumstances described above could, on a case-by-case basis, read this book, but they may not necessarily find it enjoyable. My feeling is that boys would like it more than girls because of the hunting and battling, but that is just a theory.

The Cricket in Times Square, by George Selden

A country cricket is taken in by human and animal friends when he is suddenly transported to NYC's Times Square, and he learns to play human music with his cricket legs, to the delight of all.

Why I picked it up: A cousin recommended this book at the inaugural "Beer and Books" meeting as a work he would recommend everyone to read.

My impressions: This is a very sweet book and a quick read. It kept a moderate, steady pace but still had the power to touch the emotions, especially at the end. Younger readers, perhaps third grade or so, could probably read this book, but I could see this being a fun family read-aloud because of the unique humans and the delightful animal characters. Full-page illustrations depict very well what the author describes in the text. I'd recommend this book to children as well as to any adults who want a little, relaxing tale to read.

The Secret of White Stone Gate, by Julia Nobel

This sequel to "The Mystery of Black Hollow Lane" follows more adventures of Emmy and her friends as she tries to outwit the evil organization of the "Order of Black Hollow Lane." Emmy returns to her British boarding school thinking her run-ins with the Order, but soon finds herself blackmailed - and her dear friends and loved ones threatened - when word leaks out that she still sometimes has contact with her father.

Why I picked it up: I enjoyed reading the first book about a month ago and felt the mood to read the sequal.

My impressions: Again, this book was very enjoyable. I did not realize it would be such a quick read, but I finished it within a day. I enjoyed seeing the same beloved characters from the first book, as well as meeting new villains and allies. Some of the enchantment was - perhaps not gone, but maybe changed - from the first book because Emmy was no longer learning about a secret society, and the fun exploration that accompanies such an adventure had changed into a more standard, "How do I outwit the bad guys?" problem. With that being said, I thought the problems Emmy faced, both the blackmailing Order and her uncertainty about the care of an absent loved one, gave the story a greater focus and the plot a real impetus. I appreciated the author keeping me surprised, particularly regarding a few characters I definitely thought I had figured out, and I'm looking forward to reading the next installment when it comes out in a year or two (or more?). The few complaints I have about this story are Emmy's determination to resolve her difficulties by herself, or with only her peers. She does not confide in trusted adults about her problems and takes on the responsibility and danger of protecting her loved ones all on her own - which she can't do. On several occasions, she lies and practices deception to get results. I would recommend this book to middle school readers and older who have read the first book.

Tolkien, by Humphrey Carpenter

Carpenter, the editor who put together a collection of Tolkien's letters, wrote this "approved" biography of J. R. R. Tolkien, the world-renowned author of "The Hobbit" and "The Lord of the Rings".

Why I picked it up: I read Carpenter's collection of Tolkien letters multiple years ago, and ever since a galpal told me at the time that she had read the biography written by the same man, this book has been on my "to-read" list.

My impressions: I felt that this book did justice to Tolkien's life. The author made a few self-conscious comments about the limitations of a biography as regards understanding his imagination, etc., but I appreciated his honesty and the brevity of those comments. The focus was on Tolkien. I felt like I actually got to know Tolkien, including his faults and accomplishments and virtues. Seeing this full picture of Tolkien (whom Carpenter had actually met) was a surprisingly refreshing perspective, differing from other biographies I've read that fall victim to some level of hero-worship and fail to show the difficulties of his personality (Tolkien was quite perfectionistic, tended to neglect deadlines, and sometimes or failed to complete projects to which he had committed). Carpenter's description of Tolkien and his life didn't shy away from difficulties, but I think this method endeared the subject to me all the more - to the degree that I teared up when he died, as if, indeed, Tolkien had been a beloved character in a story I was reading. I felt awed and inspired to write and itching to go back and reread "The Lord of the Rings" all at once. I'd recommend this book to any mature high school student or older who wants to learn more about an amazing author. I say "mature" high school or older for two reasons: there are a few comments about homosexuality just in passing (e.g., about certain school cultures) and the book is long enough, with only some of the later chapters actually dealing with the books he became known for - much of the book deals with his life as an Oxford don, studying philology (so if someone only wants more "Lord of the Rings" matter, this is not the book for them).

The Medieval Castle, by Don Nardo

This book, a part of the "Building History Series", gives the basics of castle history and development, building, layout, and warfare.

Why I picked it up: I need to complete research on Medieval times and castles for a project I am currently working on.

My impressions: Truth be told, I skipped the first chapter (fortresses and warfare of antiquity) because it was not relevant to my studies. Regarding the rest of the book: I found the information useful to my purposes, specifically that found in the chapters about the building of a castle and the different rooms in a castle. The black-and-white illustrations and pictures aided my understanding, but I wished there were more of them, and in color. This book comes from the "junior" section of the library and I found that Nardo did a nice job of explaining unfamiliar terms and even provided helpful pronunciation guides at times. A glossary in the back defines unfamiliar terms, although these terms were well-explained in the text. All this being said, this is not necessarily a book I would recommend to someone unless they were doing low-level research on this topic (like me). The text is informative, but not particularly attention-grabbing. I think there are other books - perhaps with better illustrations - out there that would be more fun for children who want to learn about castles, and the sources referenced by Nardo might be of even greater use to the more serious researcher than this book is. I still don't know what castle dungeons were like, or even if they typically had them, which was one of the questions I came to this book hoping to learn.

Emily's Quest, by L. M. Montgomery

The third and final book in the "Emily of New Moon" series describes Emily's growing literary achievements and her struggle to marry the right man.

Why I picked it up: I was in the mood to finish the series.

My impressions: I read this book during an intense six-hour period and I'm not sure that was a good idea. The book held my attention throughout (barring a few passages that described the scenery that I skimmed past), but the tension of waiting for Emily to get things figured out and hoping for things to turn right did not feel entirely satisfied by the predictable happy ending. I think Emily's pride was very evident in this book from the way she refused to make her attachment to her sweetheart known; it was very frustrating for me, as a reader, to watch her make assumption after assumption and not attempt to communicate honestly or rectify the situation. The ending was "happy", but rather than finishing with the good feeling I was hoping for, I think that I'm walking away from this third book with more of a "cautionary tale" feeling. It was like watching the trainwreck of "The Scarlet Pimpernel" communication fiasco, but worse because it was dragged out so long. Even resonant passages about Emily's navigation (and ending) of relationships were not enough to make up for the mistakes made by so many characters. There was a more depressed tone in this book than in the previous two in the series, and I was very disturbed by a mention of someone having watched a terrible sacrilegious event happen, even though it was a somewhat passing comment. I would recommend this book to those who had enjoyed the first two books, so long as they were in high school or above, owing to the concerning comment and heavy relationship-focus; maybe other readers would find more overall enjoyment in it than I did.

The Heart of a Samurai, by Margi Preus

Manjiro, a teenager in isolated Japan, encounters the Western world after he and his fishing companions are shipwrecked on a deserted island and rescued by an American whaling boat. Manjiro, dubbed "John Mung", learns to sail, decides to go to America, receives an education, and then returns home to Japan after many years. His reports of the Western world and his work helped Japan move into the modern era.

Why I picked it up: I found myself with access to Amazon's Kindle Unlimited program and thought this book looked interesting.

My impressions: The book was a decently interesting read, but not necessarily one I feel like picking up again any time soon. I thought the author wrote about the tension between isolationist Japan and the Western world very well. She showed the disparities between the cultures without judging one as better than another. I read with the sense that Preus did a lot of research and tried to stay true to historical events, indicating in a summary note which characters she had made up. I think her matter-of-fact narration style lent itself to a retelling of the life of a historical person, and much like the author of "Carry On, Mr. Bowditch", I found that personalities can be distinct (though perhaps a little flat). However, I did think that this style contributed to a feeling of abruptness at the beginning, and the pacing at the end - skipping over large periods of time once Manjiro has returned home - did not fit with the pacing of the book leading up to that point. I found a comment about missionaries a little concerning - Manjiro observes at one point that indigenous people have to change their entire lives for missionaries, with the result that a negative value is at least implied on missionary evangelization efforts. While undoubtedly a true observation to some degree, I felt that this was one of the few instances in which Preus did not give a balanced view of some issue. Perhaps she was just giving voice to a presumed or recorded opinion of Manjiro Of greater concern to me was a scene at the end of the book when Manjiro and his companions have returned to Japan and they are presented with a fumi-e, an image of Mary and baby Jesus that they were instructed to stomp on, in order to show that they rejected the Western religion. The scene is short, but no more context is given than what I just stated here; Manjiro tells his companions to do what they are told so that they can hopefully be released, and they all do so. As a Catholic, this part was very sad to me, of course, and it would be good for parents to be aware of this scene in particular. It was not clear to me if Manjiro ever professed the Christian faith during his time in America or not, although he is described as attending church with his adopted American parents. This book would probably be alright for a middle-schooler to read as long as parents were aware of the few concerning elements.

The Railway Children, by E. Nesbit

Three children - Roberta (Bobbie), Peter, and Phyllis - have many adventures amongst themselves and with others at the train station near their new house, which they live in with Mother while Father is mysteriously away.

Why I picked it up: A friend said a movie version is on Amazon Prime and she recommended that I read the book/watch it.

My impressions: This book falls into the category of "plotless account of everyday summer adventures enjoyed by children." Unfortunately, this is a genre that has never really appealed to me, although I understand that this style of book is beloved by many others. This book was almost one that ended up in the final section, "Books Attempted and Put Down", but I did catch my second wind and finish it up. I think the second half was more enjoyable than the first half, perhaps because I learned more about a mysterious grandfatherly sort of character and learned more about why the Father was absent in the second half of the book. Quite frankly, I found the first half irritating, probably mainly because of their Mother. She was often very sad, but expected her children to be good and not ask questions without knowing why their father was gone, why they had to move, and why they were poor. I do think children should obey and do things without knowing every reason why - that is fair. However, I think it was a little unreasonable of the mother to give absolutely no explanation. But, as I've never been in a situation where my husband is in prison and being tried for a crime he didn't commit, I can't say that she acted wrongly - it just doesn't make complete sense to me. Mother was continuously appalled that they mention how poor they are to random people - again, I think she is justified (who wouldn't be super embarrassed?), but she keeps bringing up that they can't have things because they're poor; I feel the children blabbing was maybe not entirely out her control. Well, have I been contradictory enough? I've criticized Mother both for not telling her children enough and also for telling them too much. I think it means I think I would've switched which things I told the kids - told them about Father's troubles, but really not made anything out of being poor? I digress. I found the children delightfully real, reminding me of the interactions of the Pevensie children in the "Chronicles of Narnia" series. I would recommend this book to anyone old enough to read it who enjoys this genre, but it's not a "must-read" on my list.

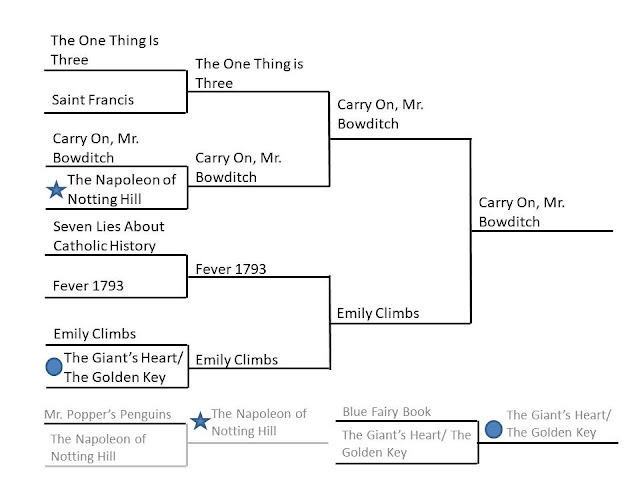

Bracket Play

An even number of books NOT divisible by four again led to a slightly lopsided bracket, but it actually helped me arrive at my decisions better than when I started with only 12 titles. The first round was very easy to determine, with weaker titles (i.e., books that I did not really enjoy and/or wouldn't highly recommend) being paired with much stronger contenders. The only matchup in the first round that wasn't a sweep was between "The Medieval Castle" and "St. Peter's Bones". I went with the second title because every part of the book was relevant to the theme, whereas "The Medieval Castle" spent its entire first chapter talking about fortifications that were neither castles nor Medieval.

In the second round, the very enjoyable "Secret of White Stone Gate" lost out to "The Cricket in Times Square" because the latter had a certain timeless quality that was lacking in the more exciting, but perhaps more frantic, "Secret". It was not difficult to decide which of the two children's historical fiction novels fell to the other. "The Sign of the Beaver" was better written, in my opinion, and I would reread it again much sooner than "The Heart of a Samurai", the latter having one very concerning scene for me. "Why I am Catholic" beat "St. Peter's Bones" because the winner was a book that I would recommend to anyone, whereas "St. Peter's Bones" would have a more limited appeal.

"Tolkien" beat "Cricket" in round three. This was a little trickier decision because the books were so different. I ended up with "Tolkien" because I have to admit that some parts of "Cricket in Times Square" were a little slow - plodding, even. The biography might share that quality at times, but it wears better in a biography than a novel (at least this time). Both books touched my emotions, but "Tolkien" was the one that I teared up for - I felt like a beloved character had perished when the biographer came to Tolkien's death. It was a close call in the match between "Sign of the Beaver" and "Why I am Catholic" - frankly, it could have gone the other way on a different day. I think that I again went with the book that I felt had a larger audience.

Finally, "Tolkien" won the prize over "Why I am Catholic" after I considered the effect that each had upon me. When reading "Tolkien", I felt inspired to read more and to create. "Why I am Catholic" was consumed more or less passively on my part, and while I felt a bit more competent about my ability to communicate my faith, I did not feel like it was something that I needed to get up and go do right now. In short, one moved me to action, and the other did not.

Books Attempted and Put Down

Adam of the Road, by Elizabeth Janet Gray/Elizabeth Gray Vining

Young teenaged bard Adam must make his way through medieval England, at times without his dog and even without his father, with whom he reunites by the end.

Why I picked it up: The usual reasons - children's lit, medieval setting, Newberry Medal Award, etc.

Why I put it down: The lack of plot in this book failed to engage me. The story wandered aimlessly, presenting encounters with various people and including unfortunate happenings, but never closing in on a major plot-forwarding problem within the first hundred or so pages. I did like how steeped the tale was in history (I learned, just for example, that the hawks used in falconry have different names depending on who owns them), but it was not enough to make me invest in the story. I think others would likely find this book a pleasant read, but I am not willing to guarantee that.